VIEWPOINT: Seeking More Working-Class Americans in Congress

The shortage of working-class politicians has consequences for economic policy, but there may be ways to encourage more to run.

Why Don't More Working-Class Americans Run for Congress?

Something historically unprecedented almost happened in Maine in 2014. In the race for the House of Representatives in Maine's second district, there was a chance that a candidate from the working class-a candidate who had worked primarily in manual labor or service-industry jobs before getting involved in politics-would replace a sitting member who was also from the working class. Troy Jackson, a state senator who works full-time as a logger when the Maine legislature isn't in session, was running for the seat being vacated by Maine Congressman Mike Michaud, a former factory worker.

If Jackson had won, it would have been the first time in American history that two former blue-collar workers had served in the same congressional seat back to back. Since 1789, House seats have changed hands more than 14,000 times. Former lawyers have succeeded other former lawyers, and former business owners have succeeded other former business owners. But a former blue-collar worker has never succeeded another former blue-collar worker in the House of Representatives.

That record remains. In June, Jackson lost his primary. When voters in Maine's second district went to the polls in November, their choices for U.S. House were a university administrator or a businessman.

Class Differences

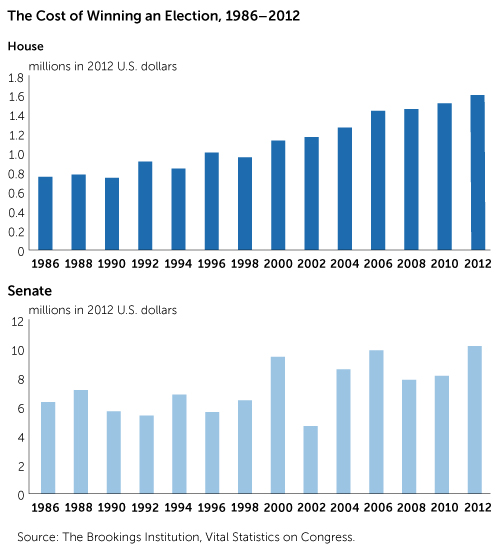

Working-class Americans almost never run for any political office, let alone in races as expensive as congressional campaigns. (See "The Cost of Winning an Election." ). If millionaires in the United States formed their own political party, that party would make up just 3 percent of the population, but it would have a majority in the House of Representatives, a filibuster-proof super-majority in the Senate, a 5-4 majority on the Supreme Court, and a man in the White House. If working-class Americans were a political party, that party would have made up more than half of the country since the start of the 20th century, but its legislators (those who last worked in blue-collar jobs before getting into politics) would never have held more than 2 percent of the seats in Congress.

The economic gulf between working-class Americans and the people who represent them in the halls of power raises important questions about our democratic process. Should we care that so many politicians are drawn from the top economic strata and so few come from the working class? Do lawmakers from different classes actually behave differently in office?

For the last seven years, I've been studying the links between the economic backgrounds of politicians and the choices they make in office. There's a school of thought in the United States that argues it shouldn't matter what our leaders' backgrounds are. "A rising tide lifts all boats." "The business of the nation is business." Regardless of our social classes, we all want prosperity, the argument goes, so what's the harm in letting affluent Americans and white-collar professionals call the shots in government?

Unfortunately, what I've found in my research is squarely at odds with such rosy ideas about class and politics. Public opinion researchers have known for decades that Americans from different economic classes tend to have different views about economic issues. Understandably, working-class Americans tend to be more progressive or proworker, and wealthy Americans, at least on average, want the government to play a smaller role in economic affairs. We may all want prosperity, but Americans from different classes may have different ideas about how to get there.

Politicians are no exception. When I examine data on how members of Congress vote, I find clear differences between legislators from the working class and those from white-collar backgrounds (that is, legislators who had white-collar jobs themselves; those raised by white-collar parents don't seem to behave differently from those raised by working-class parents, at least on average). Legislators who worked primarily in white-collar jobs before getting elected to Congress-

especially profit-oriented jobs in the private sector-tend to receive far higher scores in the Chamber of Commerce's annual ranking of members' voting patterns. Legislators who worked primarily in blue-collar jobs tend to vote the probusiness position far less often.

I find similar patterns when I examine other measures of how lawmakers behave: voting scores computed by the AFL-CIO, data on the kinds of bills lawmakers introduce, surveys of lawmakers' personal views about economic issues, and aggregate-level data on the economic policies that state and city legislatures enact. At every level of government, in every time period, and in every stage of the legislative process, legislators from different classes seem to bring different perspectives to public office.

These differences ultimately add up to a lot in the aggregate: the shortage of lawmakers from the working class tilts economic policy in favor of the outcomes that affluent Americans tend to prefer. Business regulations are more relaxed, tax policies are more favorable to the well off, social-safety-net programs are thinner, and protections for workers are weaker than they would be if our political leaders looked more like the nation as a whole. The scarcity of politicians from the working class ultimately makes life harder for the people who can least afford it.

Why, then, are there so few working-class Americans in office? To date, scholars of U.S. politics have more hunches than hard evidence. However, the data I've studied suggest that the working class itself probably isn't the problem. It's true that workers tend to score a little lower on standard measures of political knowledge and civic engagement: for instance, only about 22 percent of blue-collar workers report that they follow public affairs most of the time, compared with about 37 percent of managers and professionals. But there are still many qualified workers. If even only half a percent of blue-collar workers have what it takes to govern, that would be enough to fill every seat in Congress and in every state legislature more than 40 times-with enough leaders left over to run a few thousand city councils.

Something other than qualifications seems to keep many talented working-class people from running for office. In my research, I'm trying to pin down exactly what that is. There are many obvious suspects: differences in ambition, free time, disposable income, fundraising potential, and the like. Another important possibility is candidate recruitment. Most people who run for office are first encouraged to do so by party leaders, interest groups, and potential donors. My research (although preliminary) suggests that qualified working-class citizens are less likely to be pushed to run, even for the local and county offices that serve as gateways to state and federal government. Candidate recruitment seems to be part of the problem.

But candidate recruitment could be part of the solution, too. In New Jersey, the AFL-CIO runs a candidate-training program for working-class citizens. Since it was founded in 1997, the New Jersey Labor Candidate School has helped identify, recruit, and train hundreds of working-class candidates. The program's graduates have a 75 percent win rate and have won almost 800 elections for offices ranging from school boards to the state legislature. Similar labor candidate schools are now in the works in California, Nevada, New York, Oregon, Connecticut, and Maine.

These programs are still in their infancy, and compared with the entire scope of American electoral politics, they're only a drop in the bucket. But they seem to hold promise for increasing diversity of thought in government. In 1945, the House and the Senate were each 98 percent men. In the decades since, party leaders and interest groups have deliberately recruited female candidates, and today women make up 19 percent of Congress.

If citizens and groups that care about equality start investing in programs to recruit and support working-class candidates, someday we might see more workers running and winning-and producing economic policies that are more in step with the needs of the less fortunate. We might even see a former blue-collar worker hand off a U.S. House seat to someone else from the working class.

Nicholas Carnes is an assistant professor of public policy at the Sanford School at Duke University and the author of White-Collar Government: The Hidden Role of Class in Economic Policy Making.

Why Care Who's in Congress?

by Martin Turrin

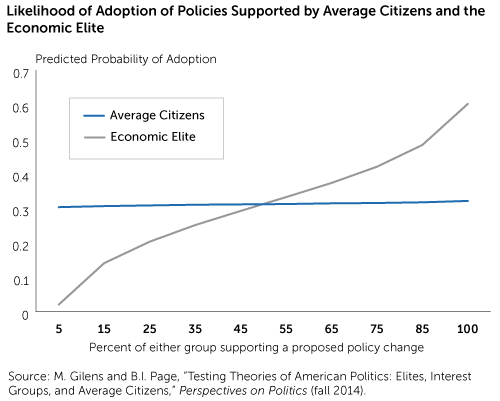

In early 2014, a Princeton study looked at the relationship between the income of those supporting a given policy and the likelihood that the policy would be adopted. The researchers surveyed the top 10 percent of earners to denote the "economic elite." "Average citizens" are those earning the median income.

When more economic elite support a given policy, there is a higher the probability of policy adoption. Increased support from average citizens for a policy change does not correlate with an increase in the chance of adopting the policy. In fact, the likelihood that a policy will be adopted remains flat, regardless of increased support by average citizens.

Articles may be reprinted if Communities & Banking and the author are credited and the following disclaimer is used: "The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston or the Federal Reserve System. Information about organizations and upcoming events is strictly informational and not an endorsement."

About the Authors

About the Authors

Nicholas Carnes